Carl Jung’s Bias Toward Spiritual Practices of the East

Many of Jung’s ideas surrounding the collective unconscious were based on his personal experiences or those of his patients. Jung admitted that his observations, as well as what he identified through his worldview as being truthful or honest, formed the foundation of his version of psychology. Many of his ideas were shrouded in personal biases, opinions, and instinctual reactions to the information he studied. Carl Jung also held specific ideas about the proper ways to interact with the collective and individual unconscious – namely through analyzing dreams after waking and through active imagination, a tool of his own creation. Carl Jung claimed to have rational reasons for his approach, but when we look deeper into C. G. Jung’s greatest contributions to psychology, we find his own work riddled with the same so-called errors that he used to disregard the ideas of others. Whereas Carl Jung was critical of other thinkers and clinicians who put forth theories without sufficient empirical evidence (statistically supported evidence), Carl Jung himself was not immune to this, regularly picking and choosing sources that fit his models.

The Unconscious

Carl Jung saw the collective unconscious as containing potential forms that we could interact with and learn from though experience (Le Grice, 2016, p. 24). Just as collective experience – the individual experiences of many – is formed by the commonalities of experience, Carl Jung observed that commonalties in unconscious experience also transcend cultures and time, creating an instinctual knowledge that can be known to individuals without being learned. This knowledge is expressed in symbols, dreams, and myths throughout history (Le Grice, 2016, pp. 23-24). According to Carl Jung, these patterns express themselves not only in stories but also in the very fabric of our reality, creating synchronistic events that Carl Jung thought related to alchemical processes (Jung, 1955/1968, pp. 464-465).

Unconscious archetypal patterns are identified by their emotional and energetic power (Le Grice, 2016, pp. 29-30). Once these archetypes are identified, the individual can study them, correlating them to specific patterns or themes in their lives. Carl Jung describes archetypes such as the Shadow, Anima, and Animus, and ultimately the Self (Le Grice, 2016, pp. 42-66). Yet with all the time and effort that Carl Jung puts into identifying these foundational archetypal patterns, he insists that we can never fully describe an archetype or the unconscious because we can identify only with its manifestation – the symbols in the dream, the mythology in the story, or the synchronistic events that play out in our lives.

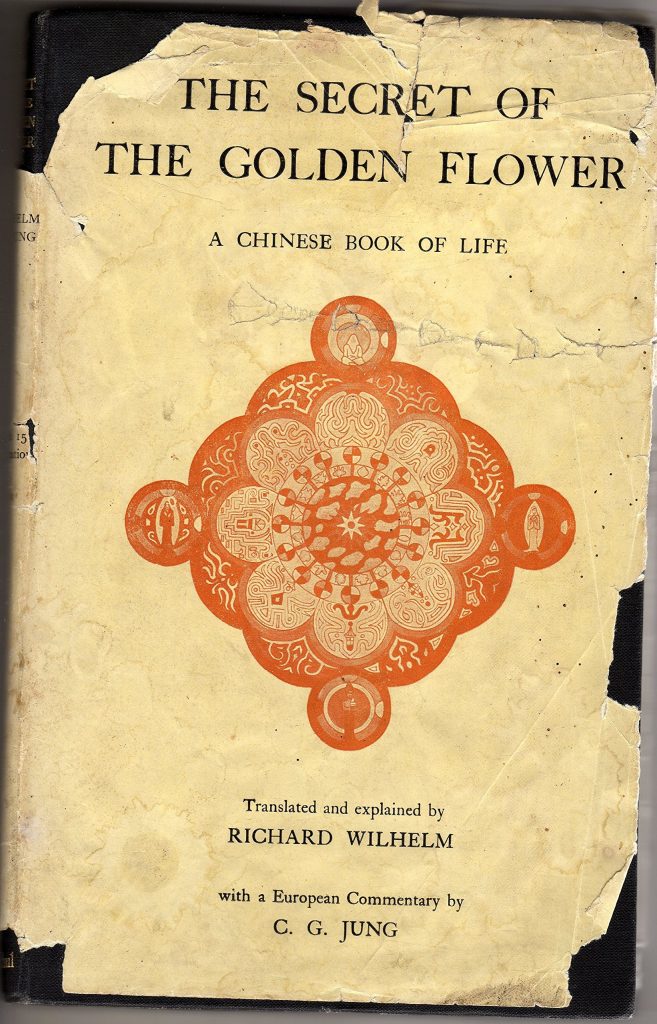

When we start to critically look at these unconscious patterns, we run into problems. According to Carl Jung, archetypes such as the Anima (the feminine aspect of a man) and Animus (the masculine aspect of a woman) were gender locked (Le Grice, 2016, pp. 48-50). As we know today, sex and gender are never black and white, as cultural influences can contribute to what a man or women should do, or be, and how they interact. We can however, rationalize Carl Jung’s statements with the generalization that most individuals do fall into distinct categories of gender; for most men, an Anima is their psychological counterpart, for women, their psychological opposite is the Animus. However, Carl Jung did not make specific generalizations about his ideas. Carl Jung also reinforces his ideas of Anima and Animus and their sex-based differences with the book The Secrets of the Golden Flower, which, contrary to what Carl Jung and Wilhelm thought, actually implied that the psychology of both men and women contained both feminine and masculine aspects which acted energetically in the human body (Lü & Cleary 1991, pp. 82-83).

Learn to Lucid Dream and Gain Rewards

![]()

Learn to lucid dream and complete tasks for re-life rewards.

Taking a look at the evidence that C.G Jung claims to have for his ideas of the collective unconscious, we find that much of what he has to say comes from his personal account or his research into alchemy and his observations of others experiences. He supports this claim by explaining that these observations are from experience and that there are enough similarities in these experiences to show that his observations are true. Yet when we inspect the sources that Carl Jung used to form his important ideas on the collective unconscious, his primary evidence seems to be anecdotal. He often extends his work past empirical research into areas of metaphysics (Main, 2014, p. 47). Carl Jung also believed that the Newtonian reductionist view was second to experience (Rowland, 2010, p. 107). Anecdotal personal experience or the accounts of his patients, however, should not be discredited, as it can provide us with important observations. Credibility comes into question, however, when selective sourcing is involved. In some of Carl Jung’s work it is apparent that he may have selected evidence that supported his views and disregarded that which contradicted them.

Jung’s Relationship to Yoga and Alchemy

C. G Jung attributes some of his ideas about the collective unconscious to his interest in Chinese alchemical yoga. A Chinese yogic and alchemical text called The Secrets of the Golden Flower, attributed to Lü Dongbin, who lived during the late Tang dynasty, inspired Jung’s interest in the practices of alchemists in the East (Wilhelm, 1962, p. XIV). He was introduced to the text by his friend Richard Wilhelm, who wrote the German translation of the book (Jung would later write the foreword). Here, at Jung’s very introduction to alchemy which inspired much of his later work on the unconscious, we see a bias toward Eastern ideas, not uncommon at the time, rooted in a Western and predominantly Christian theology (Lü & Cleary 1991, p. 82). Thomas Cleary, author of the book also titled The Secret of the Golden Flower, goes into great detail about how Wilhelm’s translation was not only flawed but contained psychological views on Chinese alchemy that didn’t exist in practice or in the original text (Lü & Cleary 1991, p. 3). Reading Wilhelm’s and Cleary’s translations side by side reveals vast differences between the translations, primarily in regard to the concept of soul.

Wilhelm translates zhixu zhiling zhi shen, which means a spirit (i.e., mind) that is completely open and completely effective, as “God of Utmost Emptiness and Life.” Based on this sort of translation, Jung thought that the Chinese had no idea that they were discussing psychological phenomena (Lü & Cleary 1991, p. 82).

Here we see one example of many in which Jung’s assumptions about the intellect of Chinese alchemists were wrong. He may have assumed that the Chinese were not advanced enough to understand the psychological implications that meditation could have on the mind of the individual and instead were primarily interested in the spirit of the individual. In Cleary’s translation of The Secret of the Golden Flower its clear to see that the Taoist practice located in the book extends past just the spiritual aspects of Chinese alchemy, but impacting the psychology of the individual as well. Jung also reinforces his ideas of Anima and Animus and their sex-based differences in The Secrets of the Golden Flower, by relating them to Yin and Yang which, contrary to what Jung and Wilhelm thought, implied that the psychology of both men and women contained both feminine and masculine aspects (Lü & Cleary 1991, pp. 82-83).

Jung takes credit for realizing that alchemy was a bridge between religion and psychology. It would seem that the Chinese alchemists were not only aware of the individual sprit but had also realized the relationship to spirit and mind well before Jung. We will see Jung’s personal and religious bias toward the unconscious and how soul and spirit play a role in that later in this paper when we delve into other alchemical texts.

Additionally, the mistranslation of The Secrets of the Golden Flower caused Jung to miss the text’s primary elements. Jung correctly ascertained that the Taoist actions were equivalent to what he called individuation, but according to Cleary, the mechanism behind this process was completely lost on Jung and Wilhelm. Though the book never fully explains the psychological results of the practice, the themes inside The Secret of the Golden Flower accurately mimic those of many other spiritual practices, including medieval alchemy as they were influenced by Chinese and other Eastern yogic traditions. By turning inward, creating a mechanism for sustaining attention while falling asleep or being at rest, and identifying with the unconscious rather than the ego, the individual is able to maintain awareness while their consciousness changes from waking to sleeping. This creates an experience that is much different from normal dreaming and that allows the person to identify with what Jung called the Self. We will later explore the similarities in these experiences with other spiritual practices.

Jung’s approach to other cultures, during his travels through Africa and India, aligns with the mindset of European colonialism, showing a disregard for other cultures and their technological or psychological advancement. This bias is an expression of a collective consciousness, as he projects his own perceived European superiority onto the other (Jung & Jaffé 1989, p. 245). Jung’s use of the words primitive and savage in describing other cultures indicates a belief that non-European cultures went about their traditions without awareness, and could not understand the link between their rituals and their psychology (Jung & Jaffé 1989, p. 241). Jung’s cultural ignorance, viewed through a contemporary lens, reduce the historic relevance and impact of his teachings.

Jung and Medieval Alchemy

The similarities between the teachings of yoga and alchemy are notable. They both were formed out of the same region of the world at the same time, most likely influenced one another, and are alchemical in nature, as they are focused on the modification of the individual’s perceived reality. Jung saw these similarities and spoke of kundalini yoga in high regard as a useful tool to understanding the collectiveunconscious.

Jung further suggests that yoga somehow is a forceful practice on the unconscious: “However, I do not apply yoga methods in principle, because, in the West, nothing ought to be forced on the unconscious of the Westerner” (Jung 1958/1968, p. 537). Here again Jung throws the baby out with the bathwater, speaking on behalf of an entire culture and asserting that the Western psyche is privileged in its ability to absorb such information directly through the mind and its resistance to inculcation. Jung then implies that his method, “active imagination, which consists in a special training for switching off consciousness, at least to a relative extent, thus giving the unconscious contents a chance to develop,” is the much better option for Westerners (Jung 1958/1968, p. 537). He implies that active imagination is a tool to be used for individuation, which is ultimately a goal to unite with the archetype of the Self while simultaneously denying yoga could be used in Western practices to similar effect.

Jung and Eastern Yoga

The word yoga means to yoke together, or bring together aspects of the self (Hughes, 2019). In this definition we do not find connotations of repressing the unconscious, as is often implied by the interpretations found in Western yogis and new age spiritual practices that are common in the new age movement. The yogis during the time of Jung’s investigation into yoga would not have a word to describe the collective unconscious as Jung saw it, but if he had taken the time to understand the culture, language, and lore surrounding yoga, he may have better understood the similarities between his ideas about the unconscious and archetypes and the philosophies conveyed in yogic teachings, specifically concerning the advice not to repress unconscious faculties. In methods similar to individuation, yogis practiced in order to move through all five layers of what they called koshas in order to reunite with the Atman, which Jung identifies is the Self (Jung, 1964/1968 p. 463).

Additional problems with yoga and Jung arise in Jung’s criticisms of other spiritual teachers who followed a Western interpretation of yoga. He disregarded the teachings of Helena Blavatsky, the founder of theosophy, and Rudolf Steiner, the founder of anthroposophy (an offshoot of theosophy), both of whose work offered initiates a way to have dream experiences that included awareness while in the dream space (Steiner page 13-37). Jung wrote positively about Rosicrucian and yoga practices, though both anthroposophy and theosophy were highly influenced by their spiritual practices. Jung insisted that students of theosophy and anthroposophy “imagine all sorts of things and assert all sorts of things for which they are quite incapable of offering any proof” (Jung, Hull, Jaffé, & Adler, 1973/1992 p. 203). Though Jung never identifies what “all sorts of things” he was referring to, much of what these two practices teach is how to use the imagination and dreaming in order to have ecstatic experiences or dreaming with awareness, something that did not fit well with Jung’s primary views of the collective unconscious.

Yoga and theosophy, however, have influenced each other throughout their modern development. Yogic teachings were chanted by certain sects in India and then largely fell out of favor for hundreds of years (Patañjali & Hartranft, 2003, pp. 1-3) until they were revived by Swami Vivekananda and theosophists for an American audience. Swami Vivekananda, a Hindu monk of the Rama Krishna order, expounded on the yoga sutras in his classic Raja Yoga. He visited the United States in 1893 as one of the first major representatives of Hinduism in the United States (“Life History & Teachings of Swami Vivekanand,” n.d.). This was the first time many Americans had ever heard of the Yoga sutras or even yoga in general.

At the time of Vivekananda’s visit (1893), America was in the middle of what would later be known as the Spiritualist Movement (1840-1920). This period was highly influenced by Theosophy and many other groups. Vivekananda was aware of this connection (Vivekananda, 2105, pp. 49-62).

Theosophy in particular was interested in Eastern ideas and claimed to have information “channeled” by hidden Eastern masters (Kilmo, 1987, p. 142). However accurate the channeling may have been, it may be assumed that many of these ideas came from the channelers’ readings of classical spiritual works. Many of these works may be regarded as authentic; however, many others came from self-styled Eastern mystics who wrote texts to fit their own understanding. A perfect example of this is William Walker Atkinson, who sometimes wrote under the name of Yogi Ramacharaka when he wanted to appear as an Indian Guru and as the “Three Initiates” when he wanted to appear as ancient hermetic teachers.

Today, and the influence of the spiritualist movement is evident in any yoga studio or New Age shop. Vivekenanda’s Raja Yoga would become required reading in British Occultist Aleister Crowley’s A.: A.: order, and thousands of modern American Yoga teachers would be required to read Patanjali during many 200-hour yoga certification programs. To say that few actually have a solid grasp on Eastern ideas would be an enormous understatement. It is a scenario where the fantasies of one culture adopted portions of understanding from another, which in turn fostered a feedback loop of misunderstanding.

It is easy to see how anyone engaging with this confusing array of beliefs and ideas could disregard it altogether. We can hardly blame Jung, who frequently discounted theosophical works in his writings, for his skepticism of these sects. However, that Jung saw through such magical thinking and snake oil salesmanship does not mean we should assume that he had any better grasp of the riddles of Eastern mysticism.

Jung’s disregard of the theosophists and anthroposophist teachings may have less to do with their spurious underpinnings and more to do with their practice of training initiates to have conscious awareness in dreams, which both Jung and Freud took issue with in their work. This is another example of Jung throwing the baby out with the bathwater. If something doesn’t fit into his narrative, he decries its usefulness.

Van Eeden and Jung

Lucid dreaming, or becoming aware in the dream, is a practice that has been taught and explored well before Jung’s time. Though Jung himself never openly discussed lucid dreaming, there is evidence that both Jung and Freud knew about it. The term lucid dream was first coined by Frederik van Eeden, a Dutch psychiatrist who published his dream journal, The bride of dreams, in the 1880s. It is eerily similar to Jung’s The Red Book. Van Eeden eventually published papers on lucid dreaming, the first appearing in 1913. Freud’s link to Van Eeden’s work on lucid dreaming appears in a number of ways. Freud mentions Van Eeden’s work in the bibliography of The Interpretation of Dreams and again mentions lucid-type dreams that he termed “sharp dreams.” We also have letters written from Freud to Van Eeden indicating that they had met and that they had some form of friendship (Rooksby & Terwee, 1990). Jung also mentions having met Van Eeden in a letter to Upton Sinclair, stating, “It was long ago, between 40 and 50 years,” and then criticized him in the same letter for being “dangerously near the modern mind, but his weakness led him into protection of the ecclesiastical walls” (Jung, Jaffé, & Adler, 1973/1990, p. 215). The sharp criticism of Van Eeden’s work by Jung may come from Van Eeden’s refusal to agree with Freud and Jung’s new psychoanalysis. It is also interesting that Jung implies that he barely knew Van Eeden but then the criticizes him for his religious views in a way that suggests they knew each other well. More likely, Van Eeden refusal to get on board with Freud’s psychoanalytical theories irritated the father of psychology and could have led Freud to discourage Jung from accepting Van Eeden’s ideas as well (Rooksby & Terwee, 1990).

Jung’s resistance and negativity toward lucidity in dreams can be explained further by Jung’s misunderstanding of the relationship between consciousness and the unconscious in yogic and alchemical traditions. In an article titled “The Great Work of Immortality: Astral Travel, Dreams, and Alchemy,” anthropologist Eric Wargo, PhD, goes into great detail about these ancient traditions and the ways in which Jung and his followers may have incorrectly assimilated their works. In many alchemical teachings, including yoga and Taoism, we have three aspects to human experience: the physical body, the etheric body or spirit, and the soul that can transfer between the two. Though awareness in these traditions is capable of leaving the body during death and ecstatic experiences, for the most part it is confined in the body while awake and dreaming. Wargo writes, “Such a tripartite division of our earthly existence into body, soul, and spirit seems remarkably universal across non-Judeo-Christian cultures” (Wargo, 2016) which is why Jung and his fellow depth psychologist may have denied the ability of the soul and spirit to be capable of merging together. Wargo continues to support his argument: “Medieval and Dark Age Europe claimed the ability, through meditative practice and sometimes use of drugs, to yoke them together and thereby achieve the feat of leaving their bodies consciously” and that “some of the most mysterious texts of 16th and 17th century alchemy show indirect or direct evidence that… alchemical adepts were also attempting precisely these difficult “journeys beyond the body” (Wargo, 2016). Wargo gives us another perspective of medieval alchemy, one of exploring the dream state with awareness through an out of body like experience.

Dream Awareness and Alchemy

In Jung’s view, the alchemist was not projecting his soul into another spiritual realm, but projecting his psyche onto objects in waking reality (Jung and the humanities, p. 112). This would further the alchemist’s development of tools to be used while awake to explore the unconscious. In the case of alchemy and Jung’s interpretation, it seems that Jung’s Judeo-Christian background and cultural influences may have closed his eyes to the idea that the soul and spirit were drastically different things and that awareness in the dream space could be not only maintained but used as a tool to uncover aspects of the unconscious. Wargo implies that both Jung and James Hillman could only recognize the unconscious as one thing and were incapable of seeing the unconscious as an experience of both spirit and soul (Wargo, 2016).

Wargo is not the only person to recognize that Jung’s assumptions about the alchemical process to be wrong. Mary Ziemer, in her article “Lucid Surrender and Jung’s Alchemical Coniunctio,” continues to bring to light similar findings on medieval alchemy and its relationship to bringing awareness into the dream space. Ziemer takes a different approach when it comes to Jung’s work, and assumes that he had never heard of lucid dreaming, saying that if he did “he would likely acknowledge that through lucid dreaming, we can theoretically facilitate [the individuation process] because we can more consciously integrate new aspects of being” (Ziemer, 2014, p. 154).

From the evidence it seems that Jung more than likely did understand that an individual can bring awareness into the dream state, that alchemy and yoga discussed this in great detail, and that others from his time wrote extensively about the ability and importance of bringing awareness into the dreamscape. He also knew the importance of this experience, but for reasons unknown to us, he did not encourage others to have these experiences in the dreaming state. If we peer into Jung’s personal dreams and life experiences, we find even more evidence of a particular aversion to lucid dreaming.

Jung’s Experiences of Dream Awareness

In Memories, Dreams, Reflections Jung describes a heart attack he had in 1944 and the resulting experiences that took place in his dreams and life soon after. He described in great detail and with clear recall of first having a heart attack and immediately having the sensation of leaving his body, going up into space, observing Earth, and then entering into a chamber where he encountered a Hindu meditating. He goes on to explain how his thoughts and sense of being were “sloughed away” in this process (Jung & Jaffé 1989, pp. 289-291). The interesting aspect of this experience is that he doesn’t go into great detail about what he thought this experience meant, if it was a dream, or if the experience was “real.” He takes it as a matter of fact. He explains it as though the experience had been real, that he somehow traveled out of his body and was in some other realm where his soul had come into contact with some alternative realm.

Jung describes life after his heart attack as being in a “strange rhythm” in which he would become awake after sleeping for a period of time and enter into a void state that was an “utterly transformed state.” This is precisely the process found to be most effective for inducing lucid dreams. He describes these states: “It is impossible to convey the beauty and intensity of emotion during those visions. They were the most tremendous things I have ever experienced” (Jung & Jaffé 1989, p. 295). He continues, “The objectivity which I experienced in this dream and in the visions is part of a completed individuation… Only through objective cognition is the real coniunctio possible” (Jung & Jaffé 1989, pp. 296-297).

Another example of a similar altered state is in one of Jung’s most referenced altered state experience in his work:

Then I let myself drop. Suddenly it was as though the ground literally gave way beneath my feet, and I plunged down into dark depths. I could not fend off a feeling of panic. But then, abruptly, at not too great a depth, I landed on my feet in a soft, sticky mass. (Jung & Jaffé 1989, p. 179)

Jung seems fully awake during this process; he is working at his desk reviewing his fears and then he suddenly feels a shift in gravity. This sudden change in the perception of space is very common in those who experience awareness in a dream state. The experience itself is so realistic that oftentimes people describe it as being more real than real; they are unable to recognize that they are, in fact, dreaming (Taylor, 2007, pp. 15-37). Sensations of falling or of being pulled down are also common in shamanic initiation type experiences, which also contains awareness in the dream experience brought on by practices similar to those of yoga, alchemy, and occult practices (Eliade, 2004, p. 61).

In all these examples we find Jung realizing through his own personal experience of awareness in the dream state that these are utterly realistic in their content, that they can happen to individuals while having a Near Death Experience (NDE) or while dreaming and while meditating, and that this experience is transformative and has a relationship to the alchemical process of coniunctio. It’s interesting that Jung not only has lucid experiences, is most likely well read on the subject, but ignores the possibility for this to be a useful technique in depth psychology. Jung’s NDE and subsequent dreams are similar not only to others’ lucid dream experiences, but also to those practices of theosophy which Jung dismissed in his earlier work.

These few examples of Jung’s dreams do not even come close to the number of references he makes to his dreams, which suggests that he brings a level awareness into the dream that go past those of typical nightly dreams. Anyone who understands the basics of lucid dreaming and out of body experiences would be astonished to learn that Jung never mentioned lucid dreaming per se.

Conclusion

Jung was a man of his time, and because of that, in hindsight a number of problems are inherent in his investigation into yoga traditions and the transcendental process of alchemy. His resources were limited to the books that he was able to purchase and his friends and colleagues who provided him the information he needed to conduct his research. And because of the cultural biases he was steeped in, it seems he was not inclined to look beyond those resources. He brought a colonialist point of view to his investigations of non-Western spiritual practices, and that point of view was then baked into depth psychology. We saw examples of such bias in Jung’s visits to other countries and in his attitude toward yoga and alchemy, cherry-picking those that were in accord with his psychological views and rejecting those which did not.

In retracing his steps, it’s easy to see now that Jung was aware of practices such as lucid dreaming and having awareness in dreams; we also know that many of the religious and spiritual practices he used as sources placed great importance on training their initiates in these arts. It is also clear that Jung ridiculed some of these groups for their lack of empirical evidence to support their claims, though those groups had just as much historical support for their practices as Jung. Additionally, many ideas about alchemy and yoga that Jung supported were based on the very teachings that the groups he decried supported or helped develop. Finally, Jung and his perceived mentor Freud knew that having awareness in dreams was possible and may have ignored that information, either to further their own research or because it was contrary to their cultural and personal views of the unconscious and soul/spirit relationship. Jung may have benefited from being personally aware of the degree to which he himself was “hopelessly unconscious” in many respects (Jung, 2017, p. 205).

From reading many of Jung’s dreams, which seem to contain elements of awareness or themes that mimic the psychological effects that take place in the induction of a lucid dream, it is easy to say that Jung had, in effect, lucid dreams. It is impossible to know for sure that Jung understood the difference between a “normal” dream and those which contained awareness; he may have assumed that they were all the same. We know that very few people naturally lucid dream, although many can learn to become aware in their dreams. We are benefited in our time with resources that Jung could not utilize, and we must be aware of this when critiquing his work.

Jung’s work, though flawed in many ways, made great strides toward bringing the public eye back into investigating alchemy. It is because of him that we can better understand these ancient practices, locate where Jung may have made mistakes, and correct them.

References

Eliade, M. (2004). Shamanism: archaic techniques of ecstasy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Grice, K. Le. (2016). Archetypical reflections: Insights and ideas from Jungian psychology. London: Muswell Hill Press.

Hughes, A. (2019, August 21). Yogas Chitta Vritti Nirodha: Patanjali’s Definition of Yoga, Explained. Retrieved from https://www.yogapedia.com/2/8458/meditation/silence/yogas-chitta-vritti-nirodha

Jung, C. G. (1968). Mysterium Coniunctionis (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.). In H. Read et al. (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (Vol. 14, pp. 1-702). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1955)

Jung, C. G. (1968). Psychology and Religion West and East (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.). In H. Read et al. (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (Vol.11, pp. 1-526). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1958)

Jung, C. G. (1968). Civilization in Transition (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.). In H. Read et al. (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (Vol. 10, pp. 1-609). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1964)

Jung, C. G., Hull, R. F. C., Jaffé Aniela, & Adler, G. (1992). Letters. London: Routledge. (Original work published in 1973)

Jung, C. G., & Jaffé Aniela. (1989). Memories, dreams, reflections. Vintage Books.

Jung, C. G. (2017). Modern man in search of a soul. New York: Martino Fine Books/Harcourt, Brace Jovanovich.

Klimo, J. (1987). Channeling: investigations on receiving information from paranormal sources. Los Angeles: J.P. Tarcher.(n.d.).

Life History & Teachings of Swami Vivekanand. Retrieved from https://www.culturalindia.net/reformers/vivekananda.html

Lü Dongbin, & Cleary, T. F. (1991). The secret of the golden flower: the classic Chinese book of life. HarperSanFrancisco.

Main, R. (2014). The rupture of time synchronicity and Jungs critique of modern Western culture. Routledge.

Patañjali , & Hartranft, C. (2003). The Yoga-Sūtra of Patañjali: a new translation with commentary. Boston, MA: Shambhala Publications.

Rooksby, R., & Terwee, S. (1990). Freud, van Eeden and Lucid Dreaming. Exeter University, UK; Leiden University, The Netherlands, 9(2).

Rowland, S. (2010). C.G. Jung in the humanities: taking the souls path. New Orleans, LA: Spring Journal Books.

Taylor, G. (2007). Darklore. Brisbane, Australia: Daily Grail Pub.

Vivekananda, S. (2015). Lectures Vol. 3: Vedanta Philosophy Basics. Schwab, Altenmünster: Jazzybee Verlang

Wargo, Eric. “The Great Work of Immortality: Astral Travel, Dreams, and Alchemy.” Thenightshirt.com, 16 May 2016, http://thenightshirt.com/?p=2857.

Wilhelm, R., & Jung, C. G. (1962). The secret of the golden flower: a chinese book of life. Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich.

Ziemer, M. (2014). Luicd Surrender and Jung’s Alchemical Coniunctio. In Hurd, R., & Bulkeley, K. (Ed)., Lucid dreaming: new perspectives on consciousness in sleep (Vol 1). Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger. (Original work published 2014).

Lee Adams is a Ph.D. candidate in Jungian Psychology and Archetypal Studies at Pacifica Graduate Institute and host of Cosmic Echo, a lucid dreaming podcast, and creator of taileaters.com, an online community of lucid dreamers and psychonauts. Lee has been actively researching, practicing, and teaching lucid dreaming for over twenty years.

Join the Discussion

Want to discuss more about this topic and much more? Join our discussion group online and start exploring your consciousness with others like yourself

Recent Comments