James Hillman’s Archetypal Psychology

Upon first hearing the term “Archetypal Psychology”, one would be inclined to believe that it’s related to the archetypes introduced by Carl Gustav Jung. Although inspired by his works, James Hillman’s Archetypal Psychology has important deviations from Analytical Psychology.

Before delving into Jung’s depth psychology, James Hillman was a student of English Literature at Paris Sorbonne University as well as Mental and Moral Science at Dublin Trinity College. He received his postgraduate doctoral degree from the University of Zurich. After acquiring his analyst diploma from C.G. Jung Institute, he then served as its director of studies for 10 years. Trained in Jungian thought and practice, Hillman did not just accept the principles taught at the institute. He would construct his own version of depth psychology, borrowing from Jung’s framework while criticizing it (Butler, 2014).

It is because of Hillman’s unique stance that embodies and at the same time rejects Jung’s tenets that make him one of the most well-known post-Jungian thinkers. Compared to other writers inspired by the works of Carl Gustav Jung, Hillman’s work has not only gained attention in the academe but in other disciplines as well (Slater, 2012). His ideas have spread far and wide across the globe due to the numerous translations of his writings.

In the span of his 50-year long career, Hillman’s message is the same across all his works: to bring emphasis to the “soul” (Butler, 2014). His writings are a response to how psychology has become more rigid; prioritizing explanation rather than the understanding of the soul (Avens, 1980). As a result of this rigidity, it is left out from its own dedicated field of study. The goal of Archetypal Psychology is to turn psychology’s focus back to the psyche.

Learn to Lucid Dream and Gain Rewards

![]()

Learn to lucid dream and complete tasks for re-life rewards.

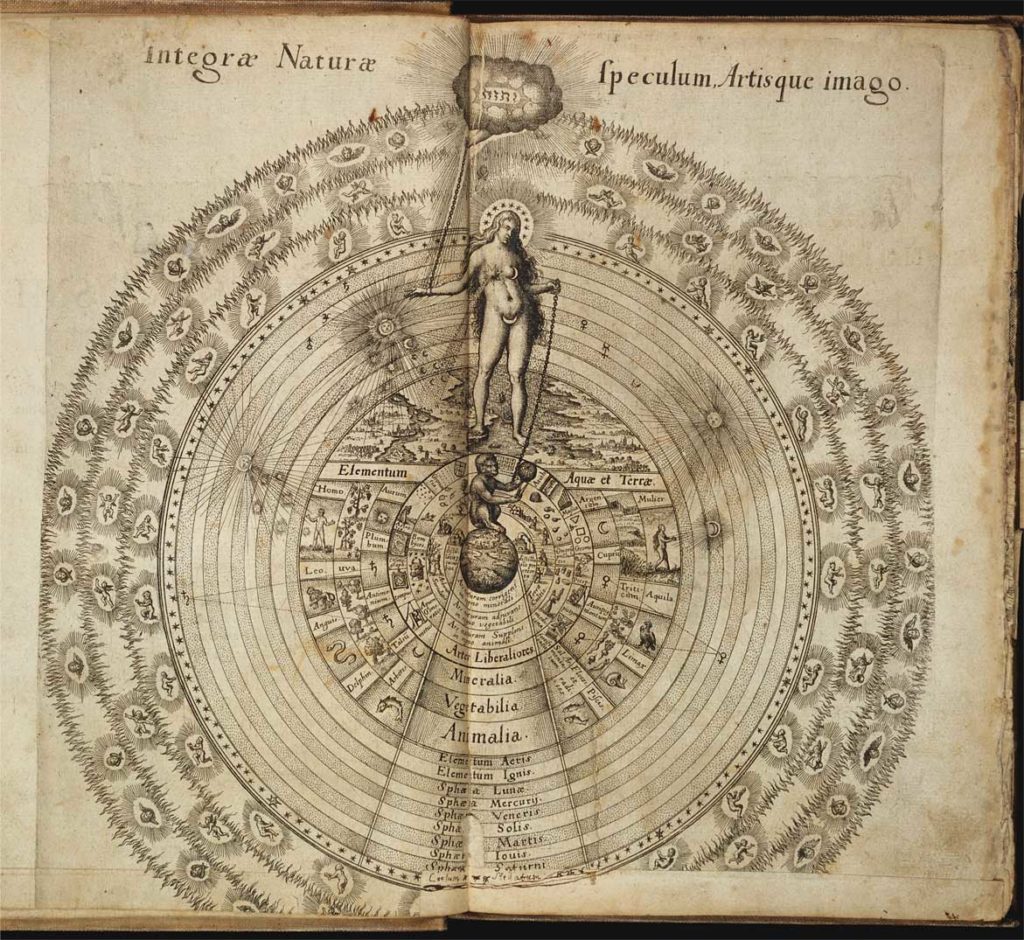

What Hillman means by psyche or soul is the “imaginative possibility of our nature, the experiencing through reflective speculation, dream, image, and fantasy – that mode which recognizes all realities as primarily symbolic or metaphorical” (as cited in Avens, 1980). It is not something that has a clear definition, nor can it be measured empirically. Hillman (1972) even goes on to say that the soul does not have strict boundaries. It is not necessarily trapped in just one body, nor does it matter which one. The psyche’s meaning and value are derived from a multitude of sources. The soul is meant to express the unknowable mysteries of life, how our psyche is connected to everything (Hillman & Moore, 1990). With Hillman’s intense regard for the psyche, Odajnyk (as cited in Tace, 2014) suggests that his body of work would be better called “imaginal psychology” than “archetypal” for the stress is on the imagination rather than the unconscious images of Jung’s archetypes.

Unlike most depth psychologies, the aim of Archetypal Psychology is not to bridge the conscious and unconscious. It is not concerned with reconciling the outside, physical world with our inner, reflective self. This is a stark contrast to Jung’s individuation which seeks to integrate the unconscious into consciousness. For Hillman, there is no division in the first place (Slater, 2012). Instead, what matters is soul-making, engagement with the images of our psyche. Indeed, Hillman agrees with Jung that “image is psyche”. According to both thinkers, images are fully meaningful in and of themselves (Avens, 1980). They are not two-dimensional objects limited to visual or auditory perception. Images can be thought of as photographs but this creates distance as opposed to when we think of images as scenes or mood (Hillman, 1978). As scenes or moods, we are more immersed in experiencing them—allowing it to affect us and vice versa. Images should not be taken literally or symbolically as Freud does. For Freud, images hold meaning because they symbolize messages of repressed sexuality (Avens, 1980). Hillman argues that there is value in the image itself. Avens (1980, p. 258) further elaborates on this by explaining that “images are not in the psyche as in a container but are the psyche. In other words, images mirror the psyche just as it is – as constantly imagining.” Archetypal psychology switches the importance of the unconscious to the imagination (Butler, 2014).

Hillman applies a polytheistic stance in his psychology which encourages us to freely explore the depths of our soul by adopting diverse beliefs, myths, and gods. This wealth of images and fantasies shape the perception of our psyche (Slater, 2012; Butler, 2014). Archetypal Psychology welcomes different modes of being all at once. However, Hillman abhors the notions of having an ego or a real self that ties together all these images (Drob, 1999). In his ideology, there is no need to integrate everything into one neat concept as seen in Hillman’s rejection of Jung’s self archetype (Hillman & Moore, 1990). The synthesis done by Jung’s self archetype was seen as restrictive by Hillman (Tacey, 2014).

Because Archetypal Psychology’s foremost purpose is soul-making, it should come as no surprise that Hillman takes on an eccentric view of pathology. He encourages us to simply embrace pathology as opposed to looking for a cure. He maintains that psychological affliction deepens and reveals the soul. In his writings, he offers no technique to alleviate any symptoms associated with mental illness and depression (Hillman & Moore, 1990). Instead, he argues that there is value in pathology, especially in the painful, distorted, appalling images that it may produce (Drob, 1999). Therapy, therefore, is not something that Hillman strongly advocates. In his interview with Fraser Pierson, he believes that therapists will force your experience into a pre-existing system that has nothing to do with pathology (as cited in Miller, 2010).

Once again challenging the psychoanalytic tendency of depth psychology, Hillman’s take on dream analysis is something that the majority is not used to. For him, the dreamer’s context or day life does not matter—only the dream is important. “Stick to the image” is his famous catchphrase when discussing the meaning of dreams. It simply means that one doesn’t have to decipher underlying messages in dreams, to do so would be reductive. He does not seek to transform the dream world into something other than itself. Hillman once said, “We cannot force the dream into any single truth. I believe I have interpreted the dream, inasmuch as the dream is its own best interpretation” (1978, p. 156-157). Society is so used to extrapolating meaning from dreams to make sense of daily life. We have been wired to think that the correct explanation of dreams is the one that fits our current belief system (Hillman & Moore, 1990). Our consciousness or ego is too preoccupied with controlling these images, unable to let go and let the psychic imagination run free (Averns, 1980).

Hillman’s approach to dreams is better likened to reading a book for reading’s sake. As a reader, you only need to follow where the story takes you. One must be fully immersed in the book’s setting and characters, without having to use these as symbols for one’s waking life. The purpose of dreams is not to deliver insight or information, but to cultivate imagination. Rather than trying to ascribe meaning to it, play with the images in your dream as if they were real entities.

Forcing it to have only one “true” meaning would already be wrong (Hillman, 1978). Hillman holds true to the polytheistic nature of his Archetypal Psychology. Uniformity is seen as a negative thing. Whether it be therapy or dream analysis – anything other than soul-making is nothing but a distraction. Other efforts take away from psychology’s true purpose which is to deepen the meaning and experience of the psyche (Drob, 1999). His approaches to pathology and dream analysis parallel one another.

Hillman is a divisive figure in the field of psychology. Many credit him as the pioneer in championing depth psychology as an “aesthetic experience” (Tacey, 2014, p.471). It’s no wonder that his works resonate more with poets, painters, and artists. The polytheistic outlook of his psychology allows us more to be authentically ourselves, without being limited to just one way of being (Drob, 1999).

However, his contributions have been faulted for being too relativistic by including everything in his scope of psychology (Drob, 1999; Tacey, 2014). This relativism makes it hard to critique his ideas that exist in its own world. Drob also cautions against Hillman’s passive stance against pathology. Leaving psychological illnesses untreated may put the person at risk for losing much more than just creativity and depth (Drob, 1999).

Upon reading Hillman, one may notice the lack of structure or hard definitions for Archetypal psychology. But if it did possess such strong boundaries, it would be contradictory to its own metaphysical nature. Hillman’s more philosophical approach is meant to question modern psychology’s valuation of therapy, behaviorism, and psychoanalytic theory. His views were intended as a catalyst to change how we see mainstream psychology. Ultimately, Hillman’s ideas implore us to examine and question the principles we hold dear. By his own rebellion against more scientific psychology, he encourages his readers to deconstruct strongly held beliefs just as he has done. And in breaking down our fixed ideals, this is yet another way in which our psyche is revealed (Drob, 1999).

Further Reading

For those who would like to look into a further critique of Hillmans views and work, it’s highly suggested that you review the article entitled Critique of Archetypal Psychology written by Mats Winther. It provides some eye-opening contradictions found in Hillman’s work in regards to Jung’s work and shows how Hillman was anti-Jungian in many aspects.

References

Avens, R. (1980). Chapter 2. Imagination is Reality: Western Nirvana in Jung, Hillman, Barfield

and Cassirer (pp. 31-47). Spring Publications.

Butler, J.A.. (2014). Archetypal psychotherapy: The clinical legacy of James Hillman. Routledge.

Drob, S. L. (1999). The depth of the soul: James Hillman’s vision of psychology. Journal of

Humanistic Psychology, 39(3), 56–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167899393007

Hillman, J. (1972). Further notes on images. Spring, 152–182.

Hillman, J. (1978). The myth of analysis: Three essays in archetypal psychology. Harper

Colophon.

Hillman, J., & Moore, T. (1990). Prologue. The essential James Hillman: A blue fire. London:

Routledge.

Miller, A. (2010). Instructor’s manual for James Hillman on the soulless society.

Psychotherapy.net.

Slater, G. (2012). Between Jung and Hillman. Quadrant, 42(2), 15–37.

Tacey, D. (2014). James Hillman: The unmaking of a psychologist Part one: his legacy.

Journal of Analytical Psychology 59, 467–485.

Ron is a neuropsychiatry intern finishing his Doctorate of Medicine. He has been in the scientific industry for nearly 10 years and specializes in curating evidence-based neuropsychiatry content. As of today, he is also teaching neuroscience to incoming doctors.

Recent Comments