Lucid Dreaming as a Method for Studying the Collective Unconscious

Lucid dreaming dates back as far as the Egyptians, most often as part of religious and spiritual practices. Such practices were intended to facilitate individuals’ connection to the divine and to the soul. In the modern day, such explorations have become largely the domain of psychology. Sigmund Freud, who is considered one of the founding fathers of depth psychology, mentioned lucid dreaming in his work. Both Freud and Carl Jung consulted with Van Eeden, an avid lucid dreamer who evangelized the power of lucid dreams to explore the collective unconscious. In developing analytical psychology, Carl Jung used several methods that supported the use of lucid dreaming, such as Chinese, medieval alchemy, yogic practices of India, and spiritual practices of the Rosicrucians.

Yet today, lucid dreaming is rarely discussed in the field of psychology, even less so in depth psychology, where discussions of dreams are commonplace. It may be assumed that psychologists pass up the opportunity to use lucid dreaming for a few good reasons. Lucid dreaming is complex and requires practice to be useful, and the techniques are not well known. Ethical questions about how to manage and facilitate lucid dreaming and about the use of various supplements known to support lucid dreaming surround the practice. There may also be questions about how much benefit lucid dreaming brings to a depth psychology practice compared with the perceived effort. This paper addresses some of these questions and discusses how lucid dreaming can be learned and used in depth psychology as a legitimate methodology for exploring the collective unconscious.

Personally, lucid dreaming is an important topic because it has profoundly impacted my personal psychological growth and my perception of reality. It has helped me to interact with different aspects of myself, and has empowered me to interface with what I believe C.G Jung would have called archetypal energies. I do not believe this would have been possible using other methods. I propose that lucid dreaming has great potential as a method of inquiry in depth psychology.

Lucid dreaming involves observing, and to some extent manipulating, the real physiological and neurological processes of sleep and dreaming. This introduces ethical issues that depth psychologists don’t typically encounter. Any action taken during waking or dreaming has an effect on the chemical structure of the individual, potentially with significant long-lasting changes to the individual’s psychology if repeated for long periods of time. This brings up important questions: Should we encourage the use of imaginative methods to interact with the psyche in seemingly unnatural ways? What is the risk/reward for those who choose to do so? What are the potential long-lasting negative effects that surround these techniques? I will address a number of these questions here.

Because lucid dreaming is an imaginative process that works both with the waking consciousness and dreaming collective unconscious as they interact with each other, this paper takes a depth psychological approach enhanced by the discipline of neurology to better understand the aspect of sleep itself. The neurological aspect of sleep is essential to understanding the process that takes place for a normal dreamer, and for those who are lucid dreaming. It also is essential in understanding why an individual may lucid dream as well as training an individual to lucid dream. Depth psychology and neurology work well together, especially in the subject of altered states of consciousness. This combination will provide readers a better overview of how lucid dreaming works, how it can be taught, its long-term positive and negative effects, and how it can be applied to depth psychology as a new method to study the collective unconscious.

Further, hermeneutics is an appropriate way to explore lucid dreaming and its related disciplines. This approach enables the collection of a large amount of information from different disciplines and perspectives and the presentation of an overall context. In developing my personal research for lucid dreaming and sleep, I have used hermeneutics to identify my blind spots, understand my frames of reference, and use other points of reference to add to the underlying truth that I am trying to identify. This is important with applied dream work, since it engages with individuals on profound levels. Using both neurology and depth psychology in context of hermeneutics can help narrow down the answers to specific questions on the subject.

A Definition of Lucid Dreaming

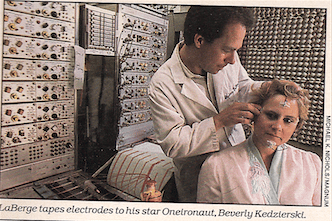

Lucid dreaming is often defined as being in control of your dream and is marketed to many looking for an escape from their daily lives into a sort of fantasy world in which they impose their ego onto the dreaming environment. However, when lucid dreaming was first defined as a term, it did not include control in the definition. Stephen LaBerge, a lucid dreaming researcher, describes lucid dreaming as simply being aware in sleep (Adams, 2020).

In their article “Varieties of Lucid Dreaming Experience” (2000), Laberge and Donald DeGracia go into great detail about what lucid dreaming is and is not. They delineate normal non-lucid dreams and lucid dream experiences by describing the level of conscious awareness individuals have in their dreams (Laberge & DeGracia) using a model proposed by Bernard Baars called Global Workspace Context Hierarchy, which makes this distinction based on the amount of sensory and goal-driven data being carried out by the nervous system (Rao, 2007).

These series of memory-based functions are similar to what depth psychology would define as the ego (Samuels, 2015). When context hierarchy is applied to the sleeping individual, depending on the focused level of that hierarchy, the individual is either aware or unaware in the dream. Of course, there are many levels of awareness in a lucid dream. An individual could be non-lucid (not yet fully aware that they are dreaming) but still attribute lucid-like characteristics to the dream, such as having self-reflection in the dream space, or remembering, sensing, or feeling something is off in the dream space (Adams, 2020).

One factor to consider is that lucid dreams take place in a field, experienced in the mind during sleep. For our purposes, we may imagine that field to be the collective unconscious. In depth psychology, its definitions range from being a repository of all human interaction to the physical framework that builds up all reality (Mijolla, 2005). The psychic framework of reality concept attributed to the collective unconscious seems the most fitting analogy in this regard. In a typical dream the interaction with the collective unconscious creates the memory experience of the dream, and we wake up from the dream to understand the dream through analysis. In a lucid dream we are aware, from the standpoint of the ego, that the dream is occurring.

While culturally, lucid dreaming is not a recognized means for interacting with the collective unconscious, the relationship between lucid dreaming and the collective unconscious is well established. It has been a feature of Tibetan Dream Yoga for centuries (Wangyal, 1998); other lucid-based phenomena such as out-of-body experiences and astral dreams are mentioned in occult communities such as the Jung-supported Rosicrucians (Lewis, 1975) and the Jung- criticized supporters of Rudolf Steiner’s anthroposophy (Steiner, Bamford, 1994) as a legitimate way to explore the collective unconscious.

Other Dream Experiences Constituted as Lucid Dreams

Since lucidity operates on a spectrum in a lucid dream, many cultures have used some form of lucid dream experience to interact with the collective unconscious. Out-of-body experiences and astral projection are just two of the terms that describe experiences on a spectrum of lucid dream (Adams, 2020). In Sylvan Muldoon & Hereward Carrington’s book The Projection of the Astral Body, they discuss the mechanisms and meaning surrounding astral projection. They describe these experiences as physical separations from the body into an energy body (Muldoon & Carrington, 1977). In his book Hacking the Out of the Body Experience Robert Peterson defines an out-of-body experience as having complete awareness while being separated from the physical body (Peterson, 2019). Robert Bruce, author of Astral Dynamics: The Complete Book of Out-of-Body Experiences, would agree partially with this simplistic definition (Bruce, 2009). It is important, however, to respect those who have had the experience and the cross-cultural commonalities of this experience is remarkably similar in that all of them feel that they have somehow separated from their physical body and are traveling outside of it.

Susan Blackmore, author of Seeing Myself: The New Science of Out-of-Body Experiences, takes a neurological and atheistic approach to the subject and overcritically explains these cross- cultural experiences as mistaken identity of spiritualism, that in fact such experiences are merely the brain’s temporoparietal junction acting up and creating a dissociative effect (Blackmore, 2019). Though researchers can create out-of-body experiences in a laboratory, it doesn’t explain why individuals have such experiences naturally while asleep.

Learn to Lucid Dream and Gain Rewards

![]()

Learn to lucid dream and complete tasks for re-life rewards.

Other dream experiences that are not categorized by typical dreams can also be experienced with lucidity. Sleep paralysis can come with hypnogogic hallucinations that are oftentimes frightening in their nature (Adams, 2020). Hobson suggests in his Activation- synthesis Hypothesis that the underlying reason for the frightening experiences is that the amygdala is super-activated in the brain while the individual transitions from stage 3 sleep to REM (Penttila, 2019). This is contested (Blake, Terburg, Balchin, Honk, & Solms, 2019).

Though neurology can explain these types of experiences to some degree, there is still the question of the subjective experiences of the content they generate. On another level, dreams can be archetypal in nature and cross-culturally experienced (Adams, 2020). For example, the negative experiences that so often accompany sleep paralysis seem very similar to Carl Jung’s description of the Shadow, and they are described by those who research sleep paralysis as the doorway to the collective unconscious (Adams, 2018). Rather than dismissing lucid dream experiences, we might allow neurology to influence a more responsible, empirically informed approach to lucid dreaming as a method for deeper awareness and individuation.

Lucid Dreaming as a Method

We can define method as a procedure or technique that provides a way of understanding a specific discipline or art (Brookshier, 2018). A method can be built out of a natural process that happens to individuals, but for it to become useful, it must be able to be learned and consistent.

There are countless books explaining how to lucid dream and a number of procedures or skills that claim high success rates. Several recent studies have found that lucid dreaming is a skill that can be learned. Laberge describes a number of techniques shown to help individuals lucid dream more consistently and increase dream recall (LaBerge, Phillips, & Levitan, 1994). Most methods with the highest success rates, including those provided by Laberge, explore waking up later in the evening when REM cycles are more prevalent and dream recall is highest (Adams, 2020).

Additionally, many of these methods sometimes take individuals only one try to have success, and for others one week is enough to yield lucid dream experiences. Lucid dreaming is already established as a safe and easy method for exploring the collective unconscious.

However, any method that involves manipulating sleep cycles obviously brings up the question of whether it is safe, as anything that incorporates changes to the “normal” operation of the human brain could yield unexpected results. As a method to explore consciousness lucid dreaming must also include methods of control.

Lucid Dreaming and the Illusion of Control

Indeed, one area of lucid dream study and methodology is how to control the dream once one is lucid. Those who experience lucid dreams for the first time are often interested in controlling some aspect of the dream; this prospect is what drives many individuals to pursue lucid dreaming in the first place. Waggoner describes that stage one out of five is attributed to personal play. This means that the individual avoids painful experiences by controlling the environment and manifesting what they desire in the dream space (Waggoner, 2009). Similarly, Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche breaks down dream experiences into three different stages including samsaric dreams, dreams which would include dreams of control. In the most simplified version of Rinpoche’s approach, there can be both lucid samsaric dreams and non-lucid samsaric dreams, but both include the dreamer’s own projection into the dream space, not the pure collective unconscious material coming to the dreamer (Wangyal & Dahlby, 1998). Jung said that the collective unconscious could never be dominated by the ego, which is self-manifested out of the collective unconscious (Schaer, 1951). If Jung’s initial ideas about the collective unconscious are accurate, then controlling the collective unconscious or elements of it in the dream space may be illusory. These impulses to control the dream, while natural, are counterproductive and antithetical to a depth psychology approach, and any training in lucid dreaming methods would have to include coaching in moving past this level and toward an openness to experience the collective unconscious—a more challenging proposition, but one with greater potential benefit.

The idea of conscious control over the unconscious is contested by the neurological community as well. According to studies by Benjamin Libet in 1979, conscious awareness is presented in a pre-filtered, packaged idea of reality that lags behind awareness. Researchers called this Libet’s delay (William, 2006). According to this principle, what we perceive as control is a story we are making up to explain the experience itself. Levitan and LaBerge explore some of the limitations of dream control in a lucid state. Their findings report that in almost all lucid dreams, some influence over how the dream expresses itself is possible, yet full control cannot be obtained. They maintain that dreams are able to be interpreted through intention rather than controlled (LaBerge & Levitan, 1993).

Interaction with the Collective Unconscious

According to Laberge and DeGracia, the amount of lucid activity during dreaming an individual can experience depends on the amount of information (from memory) they have access to while asleep; these factors influence the ability to reflect and interact with the dream space while awake. This model is similar to Jung’s active imagination. Both allow the individual to access or interact with areas of the collective unconscious while awake by withdrawing the ego from it is dominating position (Sharp, 1998).

Analytical Psychology and Lucid Dreams

Little is known about Jung’s relationship with lucid dreaming, as a concept or as a practice. The first individual to coin the term lucid dreaming was a Dutch psychiatrist named Frederik van Eeden. Both Jung and Freud knew of Eeden and his work, and some writers suggest that van Eeden’s popular 1880 dream journal, The Bride of Dreams, inspired Jung to make The Red Book (Adams, 2019).

Jung’s Memories, Dreams, Reflections tells another tale. Jung gives several accounts of lucidity in a select group of dreams. We even get a glimpse into Jung, who, after experiencing a heart attack, had what he describes as being outside of his body and seeing distances that were not possible in his waking reality (Jung & Jaffé, 1989). Later, Jung describes himself falling asleep and having a dream so real that is seemed to be reality itself. He described personal reflection while in the dream, expressing lucid-like traits of dreaming (Jung & Jaffé, 1989). With these references to lucid awareness in the dream state, it seems clear that Jung had lucid dream experiences, whether he recognized them or not.

Jung also used many different traditions with a hermeneutics approach to try to understand the overall psyche. He included Chinese and medieval alchemy and yogic practices to develop some of his techniques. Interestingly, many of these practices, unbeknownst to Jung, include some form of lucid dreaming practice. Anthologist Eric Wargo provides evidence that medieval alchemy was heavily invested in learning how to become aware in dreams and traveling through out-of-body experience (Wargo, 2019). Wargo criticizes both Jung and James Hillman for their seeming denial of this connection, attributing their blind spot to their cultural backgrounds. Mary Ziemer suggests that Jung may have overlooked lucid dreaming in his work and that lucid dreaming is an essential part of the alchemical process (Ziemer, 2014). Thomas Cleary points out methods in Jung’s Secret of the Golden Flower that resemble those from the Tibetan practice of dream yoga, something that Cleary thought was missed in the Richard Wilhelm version ultimately used by Jung (Lü & Cleary 1991). Ted Esser notes the relationship between Kundalini yoga and lucid dreaming (Esser, 2013), an important point when we consider that Jung used Kundalini in his development of analytical psychology yet warned of its use in westren psychological practice.

Despite the curious role of lucid dreaming in the development of analytical psychology, today a number of well-known depth psychologists have explored and discussed lucid dreaming as a useful practice for interacting with the collective unconscious through dream space. Founding president of Pacifica Graduate, Stephen Aizenstat, published a supportive article on the usefulness of lucid dreaming in interacting with images held in the unconscious (Powers, 2019). If active imagination is one of the primary methods of depth psychology, lucid dreaming is its natural companion and complement.

Resistance as a Method for Depth Psychology

Lucid dreaming is often misunderstood, especially by the casual observer or novice. But at its most basic level, it is a simple practice of awareness that has powerful transformative potential. It is important, then, to address questions and resistance to lucid dreaming in the depth psychology community.

Resistance to practicing lucid dreaming or encouraging clients to do so comes from several places. One may be the venerabilityof the dreamer. When ego interacts with dream content and some level of control is exerted on the normally uncontrolled dream space, the collective unconscious elements can sometimes become aggressive toward the dreamer (Adams, 2019). There is also uncertainty about one’s ability to turn off the experience when needed, especially when it becomes nightmarish. The dreamer must learn the language of the collective unconscious in the dream space to relate to and release their will and observe the dream if they are to have the dream respond well. Developing competence in this practice can take time and patience with the process and with oneself. The ability to release the illusion of control has no direct intervention; the dreamer must learn it themselves, which makes it a challenging method for anyone to explore, as it must be done alone.

Additionally, sleep paralysis and other unsettling experiences are common, and most practitioners understandably want to avoid them. Ryan Hurd (2011) writes about overcoming the fear in lucid dreams; Rudolf Steiner coined the term Guardian of the Threshold in place of sleep paralysis (Steiner, 1994). This exploration into fear and the images produced by sleep paralysis could be relatable to depth psychology’s concept of shadow work and the positive outlook toward the health of the individual who is able to work with their Shadows.

Moreover, we run into cultural and historical resistance to even agreeing on what lucid dreaming is. In depth psychology, it may be hard to define lucid dreaming as a method because it leaves so much open as to how one can lucid dream. The tools and techniques to train an individual to lucid dream can be complex and numerous. In order for a method to work, it should be consistent and repeatable, and lucid dreaming can be hit or miss—effective and easy for some, difficult for others, and inconsistent for many.

Though there are obvious issues with lucid dreaming in terms of its safety for practitioners, it is hard to say that any method used by depth psychologists to explore the psyche doesn’t come with it is own dangers. Jung warned of the dangers of active imagination, advising that it should not be conducted without supervision (Jung, 1916/1957). Yet many people use it successfully. The same can be said of lucid dreaming. It seems reasonable to say that with reward comes risk, and the individual determines what is safe or unsafe for them.

Not only does lucid dreaming explore the collective unconscious and our relationship with it, but for many it is a spiritual experience that extends into their religious space. For me, my personal exploration into lucid dreaming has been psycho-spiritual in that it has allowed me to connect religious practices, psychology, and spirituality. I have had many moments while exploring a lucid dream when I give up my ego’s will to the dream space, that the dream has produced encounters with the collective unconscious that have greatly overcome any spiritual experience I had received while in my 15 years of going to church. Jung also commented on the amazing power of being lucid in a dream himself (Jung & Jaffé, 1989).

Lucid dreams are unique in that they are easier to remember than typical dreams (LaBerge & Levitan, 1993). This empowers individuals to share dreams and archetypal material through artwork, storytelling, and therapy work. Artwork and expression in waking life can also be greatly impacted by lucid dreaming.

My passion for lucid dreaming comes from a lifetime of working with it. I have found it to be a challenging but wonderful tool to explore the collective unconscious. It is an easily learned skill that provides the dreamer with a manageable way to encounter and be positively influenced by collective unconscious and archetypal material. Though I am a new practitioner of Jung’s active imagination, I have yet to encounter the same level of communication through active imagination that can be experienced in one night of lucid dreaming.

Conclusion

Lucid dreaming is a complex subject that takes into account many cultural aspects as well as personal biases from all groups and disciplines. In this paper I have offered a definition of lucid dreaming and presented evidence for its usefulness as a method for depth psychology comparable to active imagination. I have also shown that lucid dreaming is an easily trained practice and that there are many methods for learning and practicing it. Lucid dreaming has a cultural and historical place in depth psychology that, with proper guidance, training, and support, can offer individuals a new avenue to explore the collective unconscious, individuation, and the Self.

References

Adams, L. (2018, May 12). How to Stop Sleep Paralysis, Stop sleep paralysis tonight! Retrieved from https://taileaters.com/stop-sleep-paralysis/

Adams, L. (2019, September 17). Jung’s Bias Toward Spiritual Practices of the East. Retrieved from https://taileaters.com/depth-psychology/jungs-bias-toward-spiritual-practices-of- the-east/

Adams, L. (2020, February 13). How to Lucid Dream, All you need to lucid dream tonight.

Retrieved from https://taileaters.com/lucid-dreaming/

Blackmore, S. J. (2019). Seeing Myself: The Science of Out-of-Body Experiences. Little, Brown Book Group Limited.

Blake, Y., Terburg, D., Balchin, R., Honk, J. V., & Solms, M. (2019). The Role of the Basolateral Amygdala in Dreaming. Cortex, 113, 169–183. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2018.12.016

Brookshier, K. (2018, May 30). Method vs. Methodology: Understanding the difference. Retrieved from https://uxdesign.cc/method-vs-methodology-whats-the-difference- 9cc755c2e69d

Bruce, R. (2009). Astral dynamics: The complete book of out-of-body experiences. Charlottesville, VA: Hampton Roads Pub. Co.

Esser, T. (2013). Lucid dreaming, kundalini, the divine, and nonduality: A transpersonal narrative study (Order No. 3560741). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (1357147893). Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.pgi.idm.oclc.org/docview/1357147893?accountid=45402

Hobson, J. A. (2001). The dream Drugstore: Chemically altered states of consciousness. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hurd, R. (2011). Sleep paralysis: A guide to hypnagogic visions & visitors of the night. Los Altos, CA: Hyena Press.

Jung, C.G. (1957). The transcendent function. In H. Read, et al. (Eds.), The collected works of G. Jung (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.) (Vol. 8, pp. 67-91). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1916)

Jung, C.G. (1970). The Concept of the Collective Unconscious. In H. Read, et al. (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.) (Vol. 8, pp. 67-91 pages of whole volume). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1936)

Jung, C.G., & Jaffé Aniela. (1989). Memories, dreams, reflections. Vintage Books. (Original…

Laberge, S., & DeGracia, D. J. (2000). Varieties of Lucid Dreaming Experience. Individual Differences in Conscious Experience Advances in Consciousness Research, 269. doi: 10.1075/aicr.20.14lab

LaBerge, S., Phillips, L., & Levitan, L. (1994). An Hour of Wakefulness Before Morning Naps Makes Lucidity More Likely. Retrieved from http://www.lucidity.com/NL63.RU.Naps.html

Levitan , L., & LaBerge, S. (1993, April 13). Testing the Limit is of Dream Control: The Light and Mirror Experiment. Retrieved from http://www.lucidity.com/NL52.LightandMirror.html

Lewis, H. S. (1975). Rosicrucian manual. San Jose, CA: Supreme Grand Lodge of AMORC.

Lü Dongbin, & Cleary, T. F. (1991). The secret of the golden flower: the classic Chinese book of life. Harper San Francisco.

Mijolla, A. de. (2005). International Dictionary of Psychoanalysis. Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, Thomson Gale.

Muldoon, S. J., & Carrington, H. (1977). The Projection of the Astral Body. New York: Samuel Weiser.

Penttila, N. (2019, August 26). From Angels to Neurons. Retrieved from https://dana.org/article/from-angels-to-neurons/

Peterson, R. (2019). Hacking the Out of the Body Experience. Independently published.

Powers, D. (2019, November 8). What Is Lucid Dreaming? Retrieved from https://dreamtending.com/blog/what-is-lucid-dreaming/

Rao, K. R. (2007). Consciousness studies: Cross-cultural perspectives. Cambridge: International Society for Science and Religion.

Rooksby, R., & Terwee, S. (1990). Freud, van Eeden and Lucid Dreaming. Exeter University, UK; Leiden University, The Netherlands, 9(2).

Samuels, A. (2015). Critical Dictionary of Jungian Analysis. Place of publication not identified: Routledge.

Schaer, H. (1951). Religion and the Cure of Souls in Jung’s Psychology. London: Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315009148

Solms, M. (1999). The Interpretation of Dreams and the Neurosciences. Retrieved from https://psychoanalysis.org.uk/articles/the-interpretation-of-dreams-and-the- neurosciences-mark-solms

Sharp, D. (1998). Jung lexicon: a primer of terms and concepts. Toronto, Ont.: Inner City. Steiner, R. (1994). How to know higher worlds: A modern path of initiation. Great Barrington, MA: Anthroposophic Press.

Utley, M. J. (1995). Narcolepsy: A Funny Disorder That’s No Laughing Matter. DeSoto, TX: M.J. Utley.

Wangyal, T. (1998). Tibetan Yogas of Dream and Sleep. Snow Lion Publications. Hudson, NY: Anthroposophic Press.

Waggoner, R. (2009). Lucid dreaming: Gateway to the inner self. Needham, MA: Moment Point Press.

Wangyal, T., & Dahlby, M. (1998). The Tibetan Yogas of Dream and Sleep. Ithaca: Snow Lion. Wargo, E. (2019, September 28). The Great Work of Immortality: Astral Travel, Dreams, and Alchemy. Retrieved from https://realitysandwich.com/319381/the-great-work-of- immortality-astral-travel-dreams-and-alchemy/

Wiliam, D. (2006). The half‐second delay: what follows? Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 14(1), 71–81. doi: 10.1080/14681360500487470

Ziemer, M. (2014). Luicd Surrender and Jung’s Alchemical Coniunctio. In Hurd, R., & Bulkeley, K. (Ed)., Lucid dreaming: new perspectives on consciousness in sleep (Vol 1). Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger. (Original work published 2014).

Lee Adams is a Ph.D. candidate in Jungian Psychology and Archetypal Studies at Pacifica Graduate Institute and host of Cosmic Echo, a lucid dreaming podcast, and creator of taileaters.com, an online community of lucid dreamers and psychonauts. Lee has been actively researching, practicing, and teaching lucid dreaming for over twenty years.

Thank you for a great article. I’ve been a lucid dreamer since childhood (since about age six), but I didn’t classify and diagnose my lucid dreams until I was studying psychology at university. Like previous commenters, I keenly study Jung’s writings as well as his amazing drawings. I think Jung is not wrong in his thoughts and claims about the phenomenon he calls the unconscious and its component, the collective unconscious. I have been letting the “intelligence behind the curtain” (inspired by Robert Waggoner’s Inner Self) manifest in lucid dreams for the last few years and the visions that are presented to me in lucid dreams are incredibly unexpected, symbolic, and even though it sometimes doesn’t seem like it at first (because I need some time to understand), true and inspiring. Like you, I think a lot about safety in lucid dreaming. I’ve never encountered anything dangerous myself in my really long practice, but of course that doesn’t mean that lucid dreaming can’t be risky. I fully agree with Mathew Walker (Why we sleep) that sleep and (non-lucid)dreaming is an irreplaceable and essential therapy , relaxation and regeneration for humans. I think that if we respect this, lucid dreaming should not be a risk.Therefore, I recommend practicing lucid dreaming early in the morning, when all relaxation and therapeutic sleep treatments have already taken place.

I was introduced to lucid dreaming through Carlos Castaneda, and began by taking his belief that we all have a separate dream body or dream self. I am currently not taking as much of a shamanistic view on this topic, and am avidly consuming as much Jung material as possible. This article really helped me connect the two, and I really loved the concept that this is the ego imposing itself on another level of consciousness. I have always wondered if my learned mindframe around lucid dreaming, like our worldview in waking consciousness, is influencing it for the better or worse.

Im glad it was helpful for you!