Good and Evil, Illusions of Consciousness

Understanding the Hero’s Journey, within or without, requires understanding and recognizing symbols, the universal language. Carl Jung viewed a major modern problem in psychotherapy, and thus human suffering, as the neverending list of “psychologies…since they fail to be mutually comprehensible.” (p. 29). Jung sourced this problem directly from the many ways humans seek to explain and then attack our inner demons, our Ego or Shadow, the dark part of thoughts or dreams one may wish to avoid seeing. Perhaps he is implying that within the Shadow, with its many, many monstrous faces, there is a common, albeit subtle, shared pattern and meaning behind our disparate strategies of explaining our dark sides.

Jung’s life work, in a way, was working with the symbols of his patient’s lives to help them become the Hero of their lives; he achieved this by understanding the psyche’s same underlying pattern and connecting symbols with his patients’ inner consciousness, in the process creating a possibly unified view of psychology.

My Hero’s Journey is a battle of good and evil within, the choice to actualize either self-concerned or selfless behavior externally. Yet, good and evil are not objectively or symbolically true, though they exist as widespread concepts in the human psyche. Evil, in popular terms, would be the dark side of the ego, transformed into internal or external aggression. Good is the ego/Shadow’s energy actualized into holier-than-thou directions, a kind of spiritual ego. Although we generally see “good” as being something to aim for, good tends to result further in reinforcing one’s self-image through a kind of savior-complex. Joseph Campbell describes the ego as transforming in the superego as some dragon of good and the Id as some dragon of evil. In the middle, the outcome of the Hero’s Journey, is the ego faced directly, transformed into meaningful internal and external directions.

In either case, we conceptualize our ideas, thoughts, or self-image as important. In so doing we create secrets that are hidden from the world: ideas we think are so good we don’t want to share so as to hoard them, or destructive thoughts so vile we keep them within. Kept within is the idea of sin:

“As soon as man was capable of conceiving the idea of sin, he had recourse to psychic concealment–or, to put it in analytical language, repressions arose.” – Carl Jung (p. 31)

Carl Jung likens sin in this instance to some internalization of a secret, which infects the Body like a poison, illness, cutting us off from communing socially with other humans. Jung’s conception of sin is a breath of fresh air different from, say, a Catholic conception of sin as guilt. Holding in secrets contrasts to the purpose of the Hero’s Journey as living one’s truth; withholding living our truth, keeping secrets, may be viewed as submission to our Shadow which has always been my ego unfaced, which tends to naturally go in personally destructive directions. Practically this means containing ideas as my own rather than giving freely, guarding money like a dragon, living in the mind.

In more stark terms, one might view that much illness in the body is a form of moral injury, the ego’s repression of secrets or sins, of not living one’s truth. The secret withheld is often a memory, knowledge or truism we don’t share out of fear or selfishness or, particularly for men, revealing their emotions. That repressed aspect is then sent down into the body, where it festers as a cancer might.

In my life the ego unchecked manifests as selfishness, keeping too much to myself, not listening to others. It has resulted in inflicting emotional harm to others numerous times primarily through cowardice by running from people or in letting the ego’s negative aspect escape out through the mouth, negative words directed towards others.

Can you think of any personal examples of dark aspects of your ego, however it manifests into your life? Has your ego ever caused any problems, perhaps to others as well as yourself? Has it ever resulted in forms of aggression, the Id, the normal conception of evil, directed towards yourself or others?

How about the normal conception of good? Have you ever considered yourself so self-important that only you had something to offer, some savior complex or belief that your shit stinks less than others?

The Shadow is usually emphasized in this because, in following Carl Jung’s model of the psyche, must examine the Shadow, the part of ourselves and our world we wish to avoid seeing, to face it, integrate and merge with it.

“The unexamined life is not worth living” – Socrates, Plato’s Apology

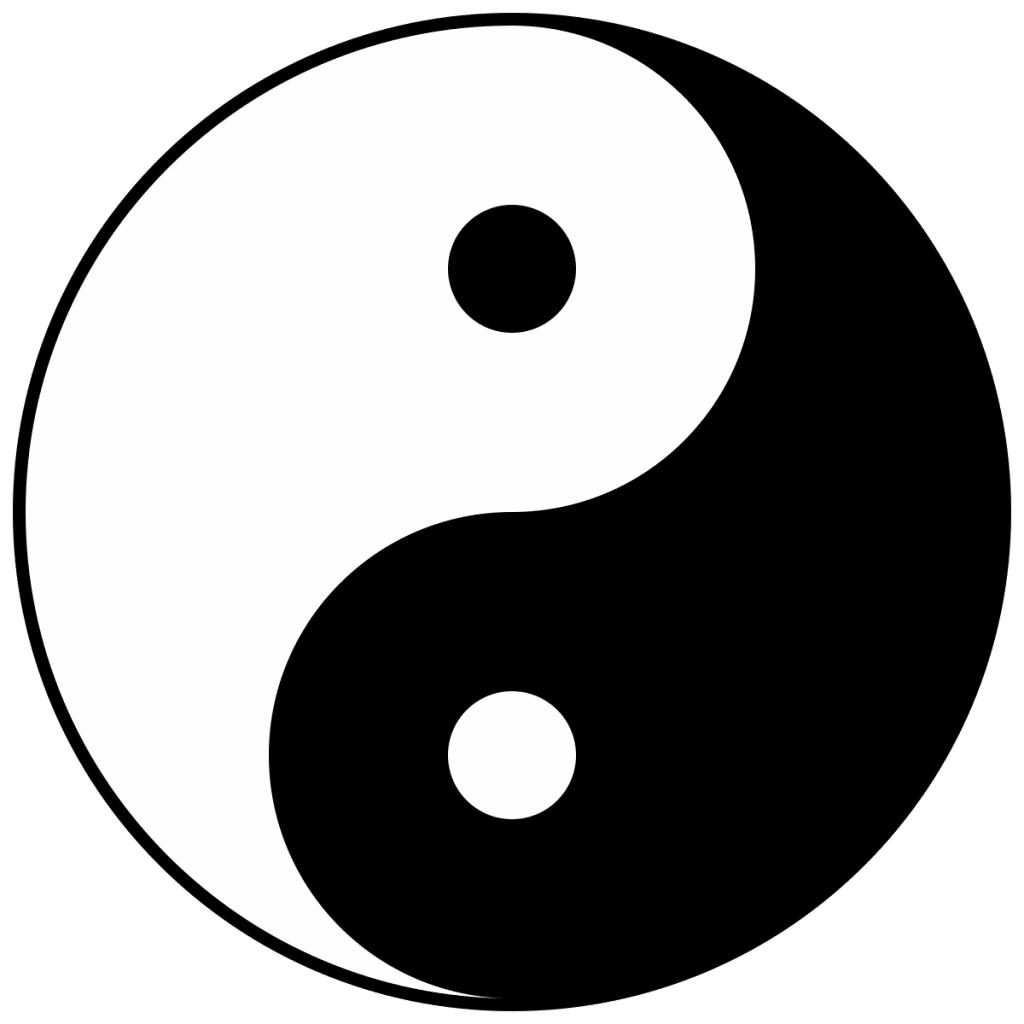

Another view of this duality and seeking the darkness within is the Yin and Yang symbol, white perhaps representing Wisdom or Order, black as Chaos; or perhaps this symbol could be seen to represent every duality. Within Order there is a speck of Chaos, symbolizing too much Order is chaotic, destructive, or that all Order has a bit of Chaos inherent within; nothing is perfect. Inside deepest Chaos, there is always some bit of wisdom to be found, suggesting there is value to seeking that which most shy away from, like Jung’s Shadow concept.

The challenging part of the psyche’s ancient battle, undertaking the Hero’s Journey, is overcoming the ego destructiveness, actualizing an individual’s truths to help build a better world rather than selfishly not giving our knowledge, abilities, and gifts. Our natural impulse is to look away in fear, for the Shadow, the dark part of ourselves, is frightening. As Melisande in A Song of Ice of Fire states often, “The night is dark, and full of terrors.” The only means through which to successfully move beyond the Shadow’s control, however, is to give up control, to face the Shadow, integrate with it.

Controlling our lives is another way of viewing the ego battle, as our ego deludes humanity into believing that we can control every part of our lives; yet, this seems an illusion. I have heard from Lee the refutation of whether we control the contents of the dreamworld and if dreams lead us where they choose; so why should we inherently assume we are able to do so in waking life? This accords with my external Hero’s Journey in which, when I “go with the flow,” my life just unravels like a trail, full of apparently random but meaningful events leading me onward further down the path; symbolized by the open, liberating, never-ending road, open to anyone at any time.

Or perhaps Light and Dark are like stars in the heavens, shining bright, against the darkness of space’s endless black. “Once there was only Dark. If you ask me, the Light’s winning.” Perhaps, or perhaps this conception, too, is a reflection of the same duality from the unified Consciousness.

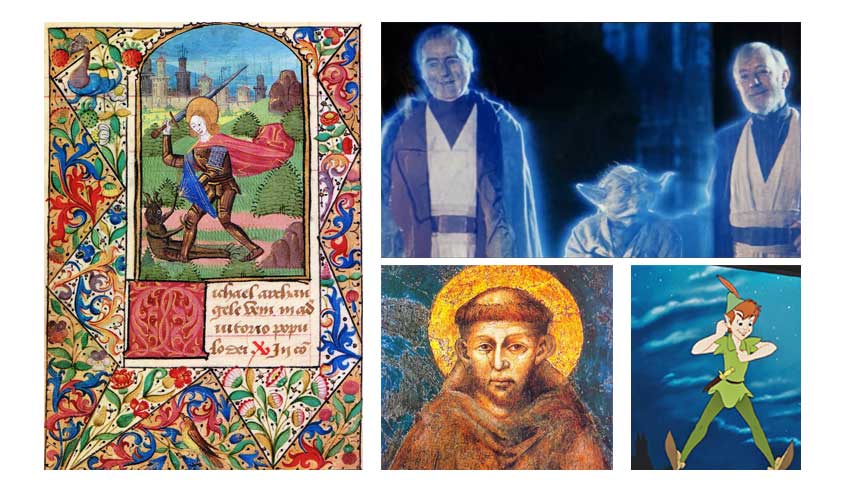

The Heart of the Battle

This painting shows aspects of good and evil quite literally as two forces battling for the Soul of a child, pulling them in opposite directions. Although the angel appears to have the upper hand in this case, the demon, the ego is always threatening, ever lurking whenever we think it is finally gone. This is the center of good vs. evil: you. Thus, we are being controlled by imagined forces, and neither are to our benefit. Being pulled anywhere is a denial of our personal truth, roped into imagined importance of self, good, or destruction, evil. Perhaps it is better to be in the middle?

This battle, born out of childhood, continues in some sense indefinitely as lesser demons perpetually pull away from the seemingly better angels of human nature. How can we truly know which ones are angels and demons? Is that not just subjective? Is not one person’s angel another person’s demon?

Consider the Democratic and Republic Parties. If you were to ask each side, one would say their side is good and the other is evil. Each would have seemingly legitimate explanations for both, as well. The same occurs in war, as one side views theirs as the good guys, while the opposition always views theirs as the good guys as well. Jung refers to this as projection, which is our tendency to project our own shadow onto others. The path out of this quandary to to realize that we all these aspects, and thus some middle ground must be found.

The Divine Inner Child

At the center of good and evil’s battle, the ego’s struggle to protect its self-image illusion in one of two equal directions lies another central image in Western symbolism. This is an archetype deep within our collective psyches: the pure, innocent child, seen in the West’s most common form of Jesus Christ.

This child represents every human as we are born, innocent and pure; connected with the spiritual world through the womb, we are torn from that spiritual world and forced to conform to this world in our earliest childhood years. To be in Western culture is to be programmed to unnatural laws and rules, and this experience is traumatic to varying extents for all children. This traumatic funneling into what is unnatural for the child results in the Ego being brought to form, to serve as representative for the inner child to this outer world. The child is then tucked away safely, locked in a treasure chest, or a prison, Egypt as the metaphorical desert of the mind, or somewhere far, far away, as the ego takes greater control and “speaks” for the Self. (Kalsched, 2013). The Self represents unity, in which our childish views of morality evaporate.

To be born a Westerner—or part of any culture now rapidly adopting Western materialism—is to become disembodied, fractured beings from how we are born. Although this is not everyone, it is many of us, men acutely, disconnected from the spiritual. As some veteran friends are apt to say, over and over: everybody has trauma.

Early Childhood

In infancy, we may live out archetypes in our conscious and unconscious world almost constantly. Campbell calls these early symbols and archetypes the guardians of the nursery in infancy, companions during the times we are alone in the crib, away from our parents while napping or being forced to sleep alone. Western children, in contrast to how children were raised in tribes, are required to spend a great deal of time alone as infants, and separate from the breast earlier as well, both of which seem unnatural. To cope with this reality, monsters of myth appear to frighten us, while fantastical creatures come to our rescue in the solitude of trying to cry ourselves to sleep. This early drama, occurring to every child left to cry themselves to sleep as individuals, demonstrates why something about all stories rings true inexplicably throughout adulthood. How this battle plays out, whether we give in to fear of the Shadow to bring out the ego or then ignore to see it transformed into the spiritual ego is likely formative to how we live our lives into adulthood.

Boys and Their Fathers

In seeking to understand myself, I learned from my mother that around age 3, the relationship with my father turned from that of “Daddy’s Boy” to being disconnected, distant. Interestingly, this is typically the time that many children start to move away from right brain dominance towards the left, suggesting our early lives are filled with creative imagery and magical symbols (Chiron et al., 1997). A kind of disconnection occurs simultaneously to this shift for those the great many traumatized in some manner in childhood, the disconnection between the brain’s hemispheres. This is a critical experience lying at the source of a modern Westerner’s life and is generally associated with a choice for the inner child to die in order to start being the person this material world wants us to be–an illusion and a lie–or to choose life, striving to live our truth irrespective of the many obstacles the modern world presents in doing so. Living this truth, embracing the chaos of seeking personal meaning, seems as chaos to others but to ourselves seems as following internal wisdom.

What is or was your relationship with your father like?

At least some fathers, perhaps a great many, start to manifest harshness towards their children around this time, forcing them to prematurely start growing up and focusing on the external world, to the absence of the interior world. Fathers may, for example, start to enforce verbal and sometimes physical discipline upon their children to veer them away from the imaginary to become as their image, a copy, molded to their selfish whims. Some mothers may do the same, though their consuming aspects seem as often directed towards daughters. This form of a parent’s enslavement to the ego, not wishing their children to become individuals but rather carbon copies of themselves, is the age-old Devouring Mother or Father archetype. In other terms this becomes the Oedipus story, a complex within every Westerner to varying extents, in which the son kills the Father–rejects the father’s identity because of an ego battle between father and son–and marries their mother by adopting their mother’s identity.

This parental identity issue, like Simba running from his father until he sees his ghost, can be part of what disrupts this Divine Child archetype. My favorite contrast to the Devouring Parent archetype is Gipetto, who wishes upon a star for the individuality of his would be son.

Has adopting your parent’s identity ever been an issue for you? Do you know of anyone in your life who fits the Devouring Parent archetype?

Dis, Disconnection

In cases of traumatic childhood experiences, such as abuse, severe loss, or maltreatment, their disconnection is driven further and further down. As the disconnection between the brain’s hemispheres widens, the monster ‘Dis’ becomes ever more powerful, the child flees further and deeper into Egypt with their father, the metaphorical desert of the Mind entrapped with their fathers because of the child’s rejection of the father. Many children remain lost, while some find their way out of Egypt by learning to atone with their father and merge, as Moses did.

Dis is the many-formed monster that appears as anything afflicting the Mind: depression, bipolar, ADHD, addiction, autism, schizophrenia, alcoholism, or being lost among the internet’s forms of Pleasure Island. Dis means to dissociate from reality, through a mental illness or addiction. Kalsched calls dissociation the archetypal bipolar inner structure, the trauma defense or the self-care system, fundamental in his view to every human psyche (Kalsched, 2013). Dis, in words, means disconnection between the two hemispheres, the analytic rain and emotional brain not communicating; and disembodiment, which is to become disconnected from the body. This deep place of suffering, our personal Hell, is the internal city at the center of Hell, filled with monsters representing the many various incarnations of the Shadow within.

Have you ever experienced one of the many forms of Dis?

For me, Dis was most often depression, negative, self-directed thoughts towards myself based on an imaginary storyline of being constantly rejected by others, a story lived since early childhood. Those thoughts kept me isolated, repeatedly, because I listened to the tyrant, my ego allowed to become Id, internalized aggression.

Consider these final images of the Divine Child as the Hero, shown as pure, clean, honest, virtuous, with a shining light around their head or even a halo. Although it is common to see these as “good,” they, like all heroes, transcend ideas of good and evil.

Can you think of any other examples in which the Hero is idealized? Can you think of anyone in your life who you hold up to as a paragon as an illuminated, real-life Hero? How about anyone in society as a whole?

References:

Campbell, J. (2008). The hero with a thousand faces. Novato, CA: New World Publications.

Chiron, C., Jambaque, I., Nabbout, R., Lounes, R., Syrota, A., & Dulac, O. (1997). The right brain hemisphere is dominant in human infants. Brain: A journal of neurology, 120 (6). Retreived from http://www.biomedsearch.com/nih/right-brain-hemisphere-dominant-in/9217688.html

Jung, C. G. (1933). Modern man in search of a soul. New York: Harcourt.

Kalsched, D. (2013). Trauma and the soul: A psychospiritual approach to human development and its interruption. New York: Routledge.

Kopacz, D. (2015). The hero’s journey. Self-published.

Andrew Haacke is a lifelong spiritual seeker who researches and writes about the Hero's Journey, symbolism, mythology, and psychedelics. He studied anthropology at the University of Utah and social work and public administration at the University of Southern California.

Join the Discussion

Want to discuss more about this topic and much more? Join our discussion group online and start exploring your consciousness with others like yourself

Thank you, this was a enlightening read. It truly helped me inderstand what I’d dreamt.